October 2016

Investigating Reports of Child Abuse & Neglect:

Has NYC Met Its Goals Set 10 Years Ago to Increase Investigative Staff and Lower Caseloads?

PDF version available here.

Summary

The tragic death last month of 6-year-old Zymere Perkins has once again focused public attention on the city’s Administration for Children’s Services and how the agency investigates reports of child abuse and neglect and monitors families already under its supervision. Unfortunately, this is not the first time the death of a child has led to scrutiny of the agency. A decade ago, after the death of 7-year-old Nixzmary Brown and the outcry that followed, a set of well-publicized initiatives was undertaken to bolster the city’s child welfare programs. These initiatives sought to improve the city’s ability to investigate reports of abuse and neglect as the number of reports increased and has stayed above the level before Nixmary’s death.

In this report, IBO looks at how the initiatives implemented in the wake of Nixzmary’s death have fared in the ensuing years. We focus on the effort to increase the number of child protective specialists—the caseworkers who investigate initial reports of child abuse and neglect—and whether the city has met and maintained the goal of lowering their caseloads and reducing the rate at which these workers leave their jobs. Among our findings:

- The number of investigative caseworkers rose quickly from 898 in June 2005 to 1,346 by June 2007. Since then the number of caseworkers has trended downward, with some year-to-year-fluctuation, in part because of a re-estimate of the number of child protective specialists needed. There were 1,216 investigative caseworkers as of June 2016.

- Although the average caseload handled by investigative caseworkers has risen over the past three years, at 10.6 in 2016 it remains below the target of 12 and well below the average of more than 16 carried by staff in 2006. But averages can mask variations among caseworkers, more than 170 of whom had caseloads of 15 or more in June 2016.

- Resignations among caseworkers increased in 2014 and 2015 but remain far below the peak levels of 2007 and 2008. The average number of years that investigative caseworkers had been in their jobs peaked in 2014 at 6.1 years from a low point of 2.4 years in 2008, and then slipped to 5.6 years as resignations and new hires increased in 2015. Nearly a quarter of the investigative caseworkers had less than a year of experience in 2015.

Following Nixzmary’s death in 2006, a large number of investigative caseworkers resigned, especially those with relatively little experience. Whether there is a spate of resignations after the latest tragedy remains to be seen. Still, it is unlikely that the number of investigative caseworkers will fall to the levels of 2005.

Background

The September 2016 death of 6-year-old Zymere Perkins, whose family had reportedly been previously investigated by New York City’s Administration for Children’s Services (ACS) for alleged child abuse and neglect, brought renewed scrutiny to the child safety practices of the agency, which has dealt with prior high-profile deaths of children under its watch. This report examines changes implemented by ACS over the last decade in the aftermath of another fatality of a child known to the agency in 2006.

Nixzmary Brown, a 7-year-old girl whose family had been reported to ACS twice previously for alleged physical abuse and educational neglect, was killed by her stepfather in January 2006; her mother was also eventually charged in the death. ACS responded to this tragedy with several initiatives intended to strengthen the effectiveness of its child protection work. A major initiative was increasing the number of caseworkers, also referred to as child protective specialists, with the goals of reducing caseloads and turnover. The agency focused particularly on those caseworkers who are tasked with carrying out abuse and neglect investigations and, to a lesser extent, on child protective specialists in the Family Services Unit (FSU), which works with families under court-ordered supervision.

This report focuses on trends in staffing among caseworkers carrying out investigations from 2005, the year before Nixzmary’s death, through 2016 (all years refer to fiscal years), in order to determine whether staffing levels and average tenure on the job increased and whether those increases were sustained over time. The report also provides background on the structure of ACS’s child protective services, a description of the abuse and neglect investigation process, and changes in the number and results of investigations over the 12-year period studied.

While focusing on investigative caseworkers, the report also briefly discusses some staffing trends and initiatives in the Family Services Unit (FSU), which came under renewed scrutiny after the January 2014 death of Myls Dobson, a 4-year-old boy whose family the FSU had previously been monitoring

Child Protective Services Structure and Process. There are four distinct areas within ACS’s Division of Child Protection Child Protective Services subdivision: borough offices, Emergency Children’s Services, the Office of Special Investigations, and Child Advocacy Centers. All four areas have child protective specialists on staff. The majority of abuse and neglect investigations are carried out in 18 borough offices throughout the city by caseworkers who carry caseloads made up of families who have been reported to the state’s hotline for alleged child maltreatment. These child protective specialists work in units, which may include specialized units that investigate only certain kinds of alleged maltreatment, such as educational neglect or sexual abuse. This brief uses the terms “investigative caseworker” or “investigative child protective specialist” to refer to these caseworkers, who are the main focus of the brief.

The borough offices also contain the Family Services Unit and the Family Preservation Program. Families under court-ordered supervision are monitored by the Family Services Unit, and the Family Preservation Program provides a voluntary and intensive case management program for families with children at high risk of abuse or neglect.

Investigative coverage on evenings, weekends, and holidays is run by the Emergency Children’s Services unit; investigations are handed off to investigative caseworkers on the next business day. The Office of Special Investigations follows up on reports of abuse and neglect involving foster parents, child care providers, and ACS staff. Finally, in each of the five Child Advocacy Centers —one in each borough—experts from the social service, law enforcement, medical, and legal fields, including staff from other city agencies, collaborate to provide services to alleged victims of child abuse in one centralized, child-friendly environment.

The New York State Central Register hotline takes reports of alleged abuse and/or neglect from mandated reporters, such as teachers and doctors, and the general public 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. Accepted reports that involve a child in New York City are forwarded to ACS and an investigative caseworker begins an investigation; the goal is to respond to the report within 24 hours.1 If a report concerns a child already involved in an open investigation, ACS has the option to consolidate the report into the existing investigation. Reports about multiple children in the same family are also consolidated into one investigation, as investigations involve the entire family, not just the child who is the subject of a report.

Child protective specialists must complete investigations and decide whether there is credible evidence of maltreatment within 60 days. If there is evidence, the investigation is referred to as “substantiated.” During the course of investigations and based on the family’s need, caseworkers offer many families referrals to voluntary preventive or community-based services, whether or not the investigation is ultimately substantiated. Preventive services are provided through nonprofit agencies contracting with ACS and are specifically designed to strengthen and stabilize families and prevent the need for removing the child(ren) from the home and placing them in foster care. The services offered include counseling, parental skills training, and substance abuse treatment. Community-based services are more general and may include anything from prenatal care or child care to help signing up for public assistance.

Even before the investigation is complete, if it appears that a child may be at risk of harm, the child protective specialist and more senior child protective staff will convene a Child Safety Conference in order to discuss safety concerns and how best to address them; the conference includes the family and any individuals the family invites for support.2 Following the conference, if there is reason to believe that court intervention is necessary to ensure the safety of the child, the child protective specialist will consult with the ACS Division of Family Court Legal Services to file a child abuse or neglect petition to seek intervention by the Family Court. The investigative caseworker will testify at the fact-finding hearing, at which the court decides whether abuse or neglect took place.

As part of the court proceeding, if ACS believes the child’s safety would be compromised by remaining in the home, the agency can request the child’s removal. The judge may approve the request to remove and place the child in foster care, or may decide that the child can remain at home or with another family member, if ACS monitors the family. This is known as court-ordered supervision, and it is when the Family Services Unit becomes involved. Family services caseworkers are responsible for visiting families at least twice a month, monitoring children’s safety, and ensuring that families comply with court-ordered requirements such as preventive services.

Investigative caseworkers can also conduct an emergency removal of a child without a Child Safety Conference and before obtaining a court order if they believe the child to be in imminent danger, but must consult with ACS attorneys to file a petition in Family Court immediately after the child is removed from the home. The request for removal will then be evaluated by the judge as described above.

Cases that remain open only for preventive services or foster care become the responsibility of the agency under contract to provide the services and ACS no longer directly works with the family unless they are under court-ordered supervision. However, ACS does oversee the general performance of these contracted agencies. (See IBO’s 2011 report on preventive and foster care services.)

Responses to Child Fatalities. Nixzmary Brown’s death in 2006 sparked a public outcry, with newspapers, citizens, and public figures asking why ACS had not been able to protect her. ACS responded by immediately reviewing the performance of the child protective specialists and supervisors who had investigated her family as well as other families in which a child later died. Ultimately, 14 ACS staff members, including caseworkers, supervisors, and one manager, had their employment terminated or faced other disciplinary action, and the agency made several leadership changes within the Division of Child Protection. The city’s Department of Investigation was also asked to examine ACS’s child safety practices.

In addition, the Bloomberg Administration created an Interagency Task Force on Child Welfare and Safety to evaluate existing partnerships among ACS, the city’s Department of Education, and the New York Police Department. In order to improve communication among these agencies as well as others that serve vulnerable children and families, the Bloomberg Administration established the Office of Family Services Coordinator. ACS was ordered to review all of its open abuse/neglect investigations and funding for the agency’s Division of Child Protection was increased by $16 million (22 percent).

ACS used this increased funding for several initiatives. The most notable—and most expensive—initiative was to add hundreds of new investigative caseworker positions. The agency also added other new staff positions, including additional training personnel, child protective managers, and attorneys, and brought in national child welfare experts to consult on child safety practices. Twenty former police department investigators were hired to assist child protective specialists and to conduct criminal background checks on all investigated family members. To strengthen casework practice, the agency overhauled its child protective specialist training and instituted ChildStat, a new data tracking and casework review system.

ACS had originally planned to focus its new hiring efforts on the Family Services Unit in order to increase the number of families under supervision after an investigation is complete.3 Due to a sharp and sustained increase in abuse and neglect reports that required investigation after Nixzmary Brown’s death, the agency’s major priority instead became lowering average investigative caseloads from nearly 17 in 2006 to a goal of 12. ACS therefore directed its increased hiring and training resources toward investigative caseworkers, and additional FSU hiring did not get underway until a year and a half later.4

Over the next several years, there were additional fatalities of children whose families had been investigated by ACS, most notably that of 4-year-old Marchella Pierce in 2010. Her death also triggered changes at ACS, but most were within the agency’s preventive services division rather than the Division of Child Protection. Other fatalities did not receive as much attention from the media or result in as many new ACS initiatives as Nixzmary Brown’s death had. In January 2014, however, Myls Dobson, whose family had previously been under supervision by the Family Services Unit, was killed by a friend of his father, stirring another public outcry. Mayor de Blasio responded by adding funding to the ACS budget for 2016 and later years to hire more caseworkers and other child protection staff in the FSU.

The de Blasio Administration also announced new initiatives to enhance child safety practices. Many of these initiatives, such as conducting a review of all open family services cases, enhancing ACS’s collaborations with other agencies, and launching a public awareness campaign to encourage individuals to report suspected child maltreatment, were similar to those begun after Nixzmary Brown’s death. In contrast to what occurred after Nixzmary’s death, however, abuse and neglect reports requiring investigation actually fell slightly in 2015, the first full fiscal year after Myls’ death, and although they then increased slightly in 2016, they were not back to the 2014 level.

In 2016, even before Zymere Perkins’ death, two reports critical of ACS’s child safety work were released: one by the Department of Investigation and one by the city’s Office of the Comptroller.5 Both reports found that caseworkers did not consistently follow the agency’s formal guidelines for conducting abuse and neglect investigations, and that supervisory oversight was often insufficient. The Department of Investigation also stated that if a new report of child abuse or neglect is made about a family under court-ordered supervision, the Family Services Unit caseworker overseeing that family is responsible for the new investigation, creating a potential conflict of interest since the caseworker would essentially be investigating their own work in keeping the child safe while the family was under supervision.

Both reports included several recommendations to ACS for improving its practice. ACS accepted most of the recommendations, including one to assign investigations involving court-ordered supervision cases to investigatory caseworkers rather than family services workers, and as of October 2016 had completed or partially completed its implementation of all of the accepted recommendations.

Shortly after Zymere’s death, Mayor de Blasio and ACS Commissioner Gladys Carrión announced a series of additional initiatives to be implemented at the agency. ACS will meet with preventive services agencies to discuss cases involving physical abuse before the agencies may close these cases. Caseworker training will be expanded, and oversight of child protective units will be strengthened. ACS will also increase staffing at the Child Advocacy Centers, which are an important component of those abuse cases that are handled jointly with the New York Police Department, and work with the Department of Education to refine its protocols on mandated reporting of suspected child maltreatment.

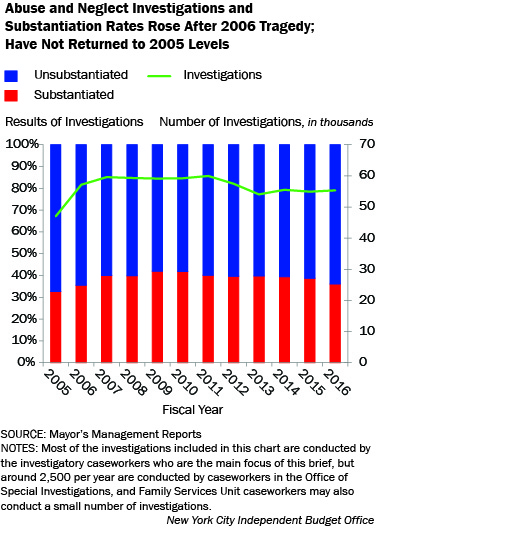

Investigations. Nixzmary Brown’s death led to a surge in the number of abuse and neglect investigations that ACS conducts each year. Although it began to gradually taper off starting in 2012, the number of investigations has not returned to the level seen before her death. Similarly, the rate of substantiated investigations was consistently higher after the tragedy than before.

The number of new abuse and neglect investigations in the city jumped from 47,021 in 2005 to 57,145 in 2006—a 22 percent increase. This was due to a number of factors, including the media attention around Nixzmary Brown’s death, which led to higher public awareness of child abuse and neglect. Additionally, the Department of Education made changes to its processes for reporting suspected abuse or neglect. The Interagency Task Force on Child Welfare and Safety and the state Office of Children and Family Services (OCFS) also launched a joint campaign to increase awareness of mandated reporting requirements and training for mandated reporters. Individuals who are mandated to report suspected child maltreatment include teachers, health and mental health providers, and child care providers. The Interagency Task Force and OCFS campaign focused on the latter two of these groups.6

ACS anticipated in 2006 that investigations would eventually return to prior levels, but that did not occur. Instead, 2007 saw another increase in investigations, to 59,615. Although investigations generally decreased from 2011 through 2015, the fewest new investigations since the tragedy—54,039 in 2013—is still 15 percent above the number in 2005.

Not only were there more investigations following the Nixzmary Brown tragedy, a larger share of investigations were substantiated. On average from 2006 to 2016, 39 percent of investigations were substantiated, a notable increase from 2005, before Nixzmary’s death, when only 33 percent were substantiated. Still, the 2016 substantiation rate of 36 percent, while 3.5 percentage points higher than in 2005, was lower than in any year since 2006.

Changes in substantiation rates may reflect actual changes in maltreatment rates, or shifts in ACS policy or practice. The overall increase in substantiation rates may be tied to closer scrutiny of the investigatory practices used by child protective specialists after the tragedy and ACS’s efforts to address shortcomings in these practices. In August 2007, the Department of Investigation released a report on ACS’s investigations of the families of several children, including Nixzmary, who had subsequently died. The report found “substantial inadequacies in ACS’s policies and procedures for investigating and responding to allegations of child abuse and neglect.”7 But it also found that in the year and a half after Nixzmary’s death, ACS had made significant progress in identifying and addressing issues with its child safety practices. In September of the same year, then-ACS Commissioner John Mattingly testified at a City Council hearing that he believed that higher substantiation rates were the result of stronger investigations.8 As referenced earlier, however, in 2016 oversight agencies including the Department of Investigation again expressed significant concerns about the thoroughness of ACS’s abuse and neglect investigations.

Spending and Funding

Spending on the area of ACS’s budget that includes investigative caseworkers increased sharply in 2006 and again in 2007 as the agency added new child protective specialists and managers. Since then spending on investigative caseworkers and managers has remained roughly constant in nominal terms and has declined over 12 percent after adjusting for inflation. From 2006 on, the largest share of funding for this area has come from federal sources.

| Administration for Children’s Services Spending on Investigative Child Protective Staff Increased in 2006 and 2007 But Then Remained Flat in Nominal Dollars, Decreased in Real Dollars Dollars in millions |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | |

| Nominal | $72.2 | $88.4 | $103.0 | $104.8 | $110.7 | $108.1 | $104.7 | $107.7 | $105.0 | $102.0 | $113.2 | $110.9 |

| Nominal: Percent Change from Prior Year | 22.4% | 16.6% | 1.7% | 5.6% | -2.4% | -3.1% | 2.8% | -2.5% | -2.9% | 11.0% | -2.1% | |

| Real (2016 Constant Dollars) | 96.1 | 113.4 | 126.6 | 123.7 | 126.1 | 120.2 | 113.8 | 114.9 | 110.1 | 105.1 | 114.8 | 110.9 |

| Real: Percent Change from Prior Year | 18.0 | 11.6 | -2.3 | 1.9 | -4.7 | -5.3 | 1.0 | -4.2 | -4.5 | 9.2 | -3.5 | |

| SOURCES: Mayor’s Office of Management and Budget; Financial Management System NOTES: Reflects only spending on key personnel titles, including child protective specialists, child protective supervisors, managers, and clerical staff, in the 0502-Protective Diagnostic budget code, which is where caseworkers who conduct investigations and carry caseloads are placed. Includes child protective specialists in training who were ultimately assigned to another area within the Administration for Children’s Services. Real dollar amounts adjusted using State and Local Government Product Deflator for New York State. New York City Independent Budget Office |

||||||||||||

In nominal dollars, staff spending in the budget area that includes investigative caseworkers rose from $72.2 million in 2005 to $88.4 million in 2006, driven by the new child protective specialist and manager positions and a $6.0 million increase in overtime pay. In 2007, as ACS continued to hire new child protective specialists and overtime pay increased by another $3.4 million, spending rose to $103.0 million, a jump of nearly 43 percent from 2005. From 2007 through 2016, spending was roughly steady in nominal terms.

The picture is somewhat different after adjusting for inflation. In real terms, spending on investigative staff peaked in 2007 at $126.6 million and remained at roughly that level through 2009. Spending then fell most years through 2014 before rising to an inflation-adjusted $114.8 million in 2015. The $110.9 million spent in 2016 was about 15 percent greater than real spending in 2005 but 12 percent below the 2007 peak.

Sources of funding for this group of staff have changed over the past decade. In 2005 this area received 39 percent of its funding from the city, 30 percent from the federal government, and 31 percent from the state. In 2006, however, it began receiving about $30 million annually from the federal Temporary Assistance for Needy Families-Emergency Assistance to Families Set-Aside for Child Welfare funding stream, and city funds were consequently reduced. Many of the initiatives following Nixzmary Brown’s death were therefore financed with this additional federal money. Excluding 2009, when ACS also received a large one-time increase to the federal Social Services Block Grant, funding from 2006 through 2016 averaged 56 percent federal funds, 29 percent state funds, and 16 percent city funds.

Family Services Unit. Family services, a much smaller group of staff, spent $14.7 million in 2005 and $33.8 million in 2016—a 131 percent increase in nominal dollars and a 73 percent increase in real terms. The biggest jump occurred between 2007 and 2008, as the unit began hiring more caseworkers and spending increased from $14.8 million to $23.2 million. The unit’s funding from 2005 through 2016 averaged 57 percent federal funds, 31 percent state funds, and 12 percent city funds.

Staffing

Number of Caseworkers. Looking at June of each year, the number of investigative caseworkers increased by almost 50 percent from 2005 through 2007, and then began to decline. Although the peak staffing level of 2007 has not been maintained, the number of investigative child protective specialists on staff each year since Nixzmary Brown’s death has remained considerably higher than before the tragedy. In 2016 there were approximately one-third more of these caseworkers than in 2005.

With new hires brought in to reduce caseloads, the number of investigative child protective specialists increased by almost a third from June 2005 to June 2006, from 898 to 1,190. By June 2007 there were 1,346 caseworkers—an increase of nearly 50 percent from 2005.

Since 2007, however, despite some fluctuations, the long-term trend has been a decrease in staffing of investigative caseworkers, with a low point in June 2014 of 1,157. A re-estimate of the number of caseworkers needed, described in more detail in the discussion of new hires that follows, contributed to this decline. Additionally, while in some years the actual staffing level has been close to the number of positions budgeted, in other years it has been well below due to delays or difficulties in filling vacancies. While the high point of 2007 was not sustained, the number of investigative caseworkers has also not come close to dipping back down to the level of 2005, and staffing has increased over the last two years studied, reaching 1,216 in June 2016.

Family Services Unit. The sustained high levels of abuse and neglect reports after 2005 necessitated a continued focus on hiring investigative child protective specialists, so new caseworkers were not added to the Family Services Unit’s budget until 2008. Between June 2007 and June 2008, the number of caseworkers in that unit jumped by 70 percent, from 204 to 347. By 2014 the number had declined somewhat to 322, although it was still almost 60 percent above the 2007 level. In response to Myls Dobson’s death in 2014, Mayor de Blasio’s 2015 executive budget included funding for approximately 130 additional child protective specialists in the Family Services Unit for 2016 and later years. Some of this hiring actually began in 2015, which saw an increase to 360 FSU caseworkers. However, 2016 spending in the FSU was below budget, suggesting that the hiring process had slowed. ACS has said that the agency hired approximately 300 child protective specialists in 2016 and will hire 175 more in fall 2017; some will be placed in the Family Services Unit, but it is not clear how many.

New Hires. In response to the outcry over Nixzmary Brown’s death and the resulting jump in investigations of abuse and neglect, ACS hired many more child protective specialists in 2006 through 2008 than it had in 2005. Since then, the number of new hires has decreased, never again reaching the level of the years immediately after the tragedy, due to a decline in the number of positions budgeted and fewer investigative caseworkers leaving the agency.

Immediately after Nixzmary Brown’s death, ACS began hiring large numbers of new investigative child protective specialists in order to decrease caseloads for these workers. ACS hired a total of 596 child protective specialists throughout the agency in 2006, nearly three times more than the 201 hired in 2005. The number of new caseworkers hired increased again in 2007 to reach 797, and remained high in 2008, when ACS added new family services caseworker positions. Many of these new workers were hired not to fill new positions, but rather to replace individuals leaving the job (see below).

In the preliminary budget for 2009, as part of citywide efforts to curtail spending in response to the revenue shortfalls caused by the recession and financial crisis, ACS implemented two budget cutbacks that resulted in fewer new hires. The cutback with the longest-lasting effect reduced the budgeted number of investigative staff for 2009 and later years. This reduction was based on a re-estimation of the time that active child protective specialists are out on annual or sick leave. With each caseworker available more of the time, fewer hires were needed to meet the caseload targets.

New hires thus began to decline starting in 2009, and although the number has fluctuated a bit since 2010, hires have never come close to the levels seen immediately after Nixzmary Brown’s death. In addition to the re-estimate of the number of child protective slots needed, part of the decline in new hires was due to fewer investigative caseworkers leaving the job and needing to be replaced. In 2015, however, new hires increased to 390 from 106 in 2014, due to an uptick in separations among investigative caseworkers, new hires in the Family Services Unit after Myls Dobson’s death, and new hires in other units that are not the focus of this report.

Separations. In all of the years studied, most strikingly in the years immediately after Nixzmary Brown’s death, resignations, rather than terminations or transfers to other positions in ACS, have made up the majority of separations among investigative child protective specialists. The number of resignations was much higher in 2007 and 2008 than in the two previous years, but then decreased until 2013, before increasing somewhat in 2014 and 2015.

From 2005 through 2015, the overall pattern of separations from the investigative child protective specialist title was largely driven by the pattern of resignations, which made up an average of 70 percent of separations. In 2005, before Nixzmary Brown’s death, resignations were only about 53 percent of all separations; this percentage has not been so low in any year afterward. The second-highest category of separations, at an average of 16 percent, has been terminations/dismissals. Finally, caseworkers who leave the title for another position within ACS—usually a promotion—have averaged 13 percent of separations each year.

Throughout the U.S., keeping child protective workers on the job is difficult, as the work can be very stressful and is not highly paid. (In 2016 the starting salary for an ACS child protective specialist was $44,755, with a raise to $48,605 after six months, to $51,830 after 18 months, and a maximum salary of $73,486.) High caseloads, administrative burdens, insufficient support from supervisors, and inadequate training are frequently cited as additional widespread problems that can lead workers to leave the child welfare profession.9 High turnover can have negative effects on the families and children served, as the cases of those who leave are given to new workers who are not familiar with the families’ situations. This can also lengthen the time it takes to complete investigations.10

From 2005 to 2006, investigative child protective specialist resignations increased by 65 percent, from 107 to 177, perhaps due to the increased scrutiny and pressure on the unit after Nixzmary Brown’s death. This jump is particularly notable because overall separations increased by only 18 percent over the same period. Resignations then rose by another 88 percent to 332 in 2007, the first full fiscal year after the tragedy.

ACS implemented several initiatives designed to boost retention as one of its early responses to Nixzmary Brown’s death. The agency modified Connections, the statewide child welfare reporting system, to make it more user-friendly and improved working conditions in the field by giving caseworkers cellphones and expanded transportation options. ACS also created the NYC Leadership Academy for Child Safety to enhance child protective managers’ supervisory practices and launched ChildStat, a weekly series of meetings still in place today, in which ACS senior staff and borough office managers examine individual cases and aggregate data trends in order to provide support to borough offices and improve agencywide casework practice. Finally, ACS overhauled caseworker training by integrating real-life child protective examples into the curriculum and creating a smoother transition between classroom training and work in the borough offices.

In 2008, ACS also modified its application and screening processes and ran its first large-scale campaign to recruit child protective specialists who were interested in child protection as a career and knew what to expect from the job. These efforts, coupled with the retention initiatives, seem to have paid off; although investigative caseworker resignations remained high at 288 in 2008, they were lower than in 2007, and continued to steadily decrease through 2013. This decrease may also have been partially due to the recession, which may have made caseworkers reluctant to leave their jobs. Resignations increased somewhat over the next two years and by 2015 the number of resignations (145), was higher than in 2005, but well below the high points of 2007 and 2008. The increase in resignations may be partly due to the improved economy, which could lead some child protective specialists to seek out other opportunities.

The agency’s latest effort to support caseworkers occurred in 2016 with the launch of the ACS Workforce Institute. In partnership with the City University of New York’s School of Professional Studies, the institute provides staff with training on core competencies of the child welfare field, including interviewing, investigation, and risk and safety assessment skills. This training is more specialized and in-depth than the more basic training that caseworkers have always received at the beginning of their time at ACS.

Family Services Unit. For child protective specialists in the Family Services Unit, resignations made up an average of 54 percent of separations from the title each year from 2005 through 2015. Leaving for a new position within ACS accounted for 25 percent of separations from the FSU, and 9 percent of separating caseworkers in this unit were terminated or dismissed. Finally, 10 percent of FSU caseworker separations were due to retirement (compared with only 1 percent for investigative child protective specialists).

These figures indicate that resignations are less of an issue for family services caseworkers than for investigative caseworkers, possibly indicating that investigation is a more stressful job. One reason for this may be that FSU staff typically work with families for 3 to 12 months or longer, while investigative staff must close their investigations within 60 days. This may allow FSU workers to engage with families more deeply and feel less pressure to turn over cases than investigative workers. Additionally, investigative caseworkers’ involvement with families occurs at a tumultuous time in their lives, when maltreatment allegations are fresh and there is a possibility that children may be removed from the home. Family services caseworkers engage with families at a typically less stressful time, when they are receiving services and children are either in the home or with relatives.

Tenure. Average tenure of investigative child protective specialists began to decrease immediately after Nixzmary Brown’s death with the simultaneous influx of new hires and the resignations of many caseworkers who were on the city’s payroll at the time of the tragedy. Average tenure continued to decline until 2008, but has since risen considerably, with a high point in 2014. Despite a modest decline in 2015, average tenure in that year was still much higher than either just before or after the tragedy.

The length of time that caseworkers stay in their position is important, since new staff need time to go through training, work up to a full caseload, and gain the experience necessary to engage with families and make informed decisions about child safety. Average investigative child protective specialist tenure in 2005 was 4.1 years, but dropped sharply over the next few years, finally reaching a low point of 2.4 years in 2008. This decrease is not surprising, given the many new workers that joined ACS during this time period.

Beginning in 2008, average investigative tenure steadily rose to a peak of 6.1 years in 2014. This is because fewer child protective specialists were leaving the position over this time period, and the number of new hires needed to prevent caseloads from exceeding the agency’s target was consequently far lower than immediately after Nixzmary Brown’s death. In 2015, as separations and new hires both increased, average tenure decreased to 5.6 years, but it was still much higher than the average right before Nixzmary’s death or for several years after the tragedy.

Looking only at average tenure can obscure changes in the shares of the workforce with the least and the most experience. The share of investigative child protective specialists with less than a year of tenure rose from 18 percent in 2005 to 44 percent in 2007 as ACS hired new staff. Since then, the annual percentage of investigative caseworkers who have been on the job less than a year has fluctuated but has consistently been much lower than the peak of 2007, although in 2015 it rose sharply from prior years to 24 percent. Conversely, investigative caseworkers with seven years or more of tenure made up only between 9 and 15 percent of all these caseworkers from 2005 through 2012, but their share increased over the next three years, reaching 39 percent in 2015.

From 2007—the first full fiscal year after the tragedy—through 2009, investigative child protective specialists who resigned from the position tended to be relatively new hires. This suggests that many of the large cohort of new hires in 2006, 2007, and 2008 quickly became unhappy with the job or were encouraged to leave. Since 2009, the average tenure of resigning caseworkers has generally increased along with the average tenure of the overall investigative workforce. This may reflect the impact of the initiatives to improve screening of applicants and revamp training.

Caseload

Average investigative caseloads were sharply higher in 2006 (16.6 cases per caseworker) and 2007 (14.9) due to the jump in investigations of child abuse and neglect following the death of Nixzmary Brown. However, caseloads in 2008 fell to an average of 11.0 per caseworker, roughly the same as in 2005, and remained below that level through 2016.

At the end of each month, ACS calculates the average caseload for investigative child protective specialists by dividing the number of open investigations by the number of caseworkers actively carrying cases (meaning that they are not on any type of leave) at that point in time. The annual average reported above is an average of these 12 monthly figures. The staffing numbers shown in the chart on this page are point-in-time figures as of June 30 of each fiscal year; these numbers fluctuate throughout the year, so average caseloads cannot be calculated by simply dividing the annual number of investigations by the number of investigatory staff at a particular point in time. Finally, average caseload is affected not only by the number of investigations and child protective specialists, but also by how long investigations take to complete.

Lower caseloads allow caseworkers to engage more deeply with each investigation and are thus associated with higher-quality investigations and higher worker satisfaction.11 In 2005 the average investigative child protective specialist caseload was 11.5; this shot up to 16.6 in 2006 due to the sharp increase in investigations. Following this spike in caseloads, ACS set a goal of reaching an average caseload of no more than 12.0, which it reached in 2008. Caseloads continued to decline until reaching a low of 8.2 in 2013. But average caseloads then increased to 10.6 in 2016—the highest level since 2008—although still below the target, as well as below the state’s target of 15.0.12

The issue of caseloads is complex, and no one factor explains all of the variation in caseloads over the years. For example, while the sharp increase in abuse and neglect investigations between 2005 and 2006 clearly caused a jump in caseload, trends in investigations and caseloads since 2007 have not always moved in tandem. Similarly, the increase in staffing from 2006 to 2007 contributed to a decrease in caseload, but both staffing levels and caseloads decreased from 2008 through 2013.

Nationwide, low caseloads are typically associated with low turnover (and vice-versa), and this held roughly true at ACS.13 Resignations and caseloads both declined from 2007 through 2013, and both increased in 2014 and 2015. Lower caseloads may improve morale, lessening turnover. Alternatively, lower turnover could lead to lower average caseloads since more experienced workers may be able to close investigations more quickly. In addition, when staff leave, the remaining workers must take over their cases in addition to their own until new staff can be hired and trained. It is likely that all of these factors are at play. There were some years, however, in which the percentage change in resignations was far smaller than the percentage change in caseloads, or

The citywide caseload averages cited above mask variation across boroughs and borough offices, and across individual caseworkers. When looking at the borough level we only have data at a single point in time (June 30 of each fiscal year) rather than the monthly data that were used to derive the citywide average annual caseloads used in the preceding discussion. As a result the average caseloads reported by borough cannot be directly compared with the citywide averages presented earlier.

| Bronx Consistently Has Above Average Investigative Caseloads; Queens Has Below Average | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | |

| Bronx | 13.6 | 11.4 | 9.3 | 10.5 | 10.1 | 9.2 | 9.3 | 12.2 | 11.8 | 12.7 |

| Brooklyn | 13.4 | 10.6 | 8.8 | 9.4 | 11.0 | 8.9 | 9.0 | 12.6 | 10.1 | 12.2 |

| Manhattan | 13.6 | 9.2 | 7.8 | 9.5 | 9.8 | 9.4 | 10.0 | 11.5 | 8.9 | 12.3 |

| Queens | 12.8 | 11.2 | 9.5 | 8.6 | 7.9 | 7.4 | 7.4 | 9.0 | 8.4 | 9.8 |

| Staten Island | 13.5 | 11.1 | 8.8 | 8.7 | 9.0 | 7.3 | 8.3 | 9.8 | 12.2 | 13.2 |

| Citywide Average | 13.4 | 10.8 | 9.0 | 9.5 | 9.8 | 8.7 | 8.9 | 11.5 | 8.9 | 12.0 |

| SOURCE: Administration for Children’s Services Child Welfare Indicators Annual Reports NOTE: Because these figures are from a single point in time (June 30 of each fiscal year), they are not directly comparable to the average citywide caseloads shown earlier. New York City Independent Budget Office |

||||||||||

Since 2007, the first year for which data on average caseloads by borough and borough office are available, average caseloads as of June 30 of each year have consistently been above the citywide average in the Bronx and generally below the average in Queens. The remaining boroughs have all fluctuated between having average caseloads at, above, or below the citywide average in various years. Additionally, each borough except Staten Island has several borough offices, and these offices’ average caseloads often vary widely even within a particular borough. This has been particularly true in the Bronx and Brooklyn, which have the most borough offices because they receive the most State Central Register reports.

Just as caseloads vary from year-to-year and borough-to-borough, they also vary across child protective specialists. Caseworkers with less experience typically have caseloads that are well below the average, as they are still learning how to do the job; in fact, after completing their initial classroom training, new child protective specialists carry reduced caseloads under close supervision for three months. Conversely, other caseworkers can have very high caseloads. In June 2007, during the surge in investigations following the death of Nixzmary Brown, nearly one-quarter of all child protective workers had caseloads above 15.

| Number of Investigative Caseworkers With Caseloads Above 15 Fell From 2007 Through 2013 But Rose Sharply in Past Three Years | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | |

| Number | 317 | 74 | 16 | 19 | 37 | 9 | 8 | 157 | 111 | 173 |

| Percent of All Investigative Case Workers | 23.6% | 5.6% | 1.3% | 1.6% | 2.9% | 0.7% | 0.7% | 13.6% | 9.3% | 14.2% |

| SOURCE: Administration for Children’s Services Child Welfare Indicators Annual Reports NOTE: Figures are from June 30 of each year (June 25 in 2016). New York City Independent Budget Office |

||||||||||

The share of investigative caseworkers with caseloads above 15 dramatically decreased from 23.6 percent in 2007 to 5.6 percent in 2008 and 1.3 percent in 2009, as average caseloads also declined. From 2014 through 2016, though, a much larger share of caseworkers had caseloads above 15; the 2016 share, 14.2 percent, was the highest since 2007

Family Services Unit. Caseloads for child protective specialists in the Family Services Unit averaged 14.8 in 2009, the first year that data is available. The average caseload steadily declined until 2013, when it reached 9.8, but then increased slightly the next two years. In all years except 2015, when average caseloads for both groups of child protective specialists were 10.5, the average family services caseload has been higher than that of investigative caseworkers. Funding added to the 2016 FSU budget was meant to reduce caseloads in the Family Services Unit to 8.0; average caseloads are not available for 2016.

Conclusion

The immediate aftermath of Nixzmary Brown’s death in 2006 saw major changes in how ACS staffed, recruited, and trained its child protection investigative function. Many new caseworkers were hired and the number of abuse and neglect investigations rose; a larger share of these investigations was substantiated. The increase in investigations led to higher average caseloads, even with the new hires. After the tragedy there were also sharp increases in resignations of investigative child protective specialists, particularly among relatively new hires, resulting in a drop in the average tenure of these caseworkers. More recently, Myls Dobson’s death in 2014 led to a call to bolster staffing in the Family Services Unit, but this effort may have gotten underway more slowly than anticipated. The recent death of Zymere Perkins has brought renewed scrutiny of ACS’s child protection investigation work, particularly around staffing and supervision.

Some of the changes spurred by Nixzmary’s death have lasted, while others have not. The number of investigative caseworkers seems unlikely to dip back down to levels seen before her death. Similarly, there have been many more abuse and neglect investigations every year after the tragedy than before, suggesting that campaigns to increase public awareness of child maltreatment and how to report it have become more effective. While average investigative caseloads rose in the last three years studied, they remained below ACS’s target of 12 and well below caseloads in 2006 and 2007. On the other hand, averages can mask variation among caseworkers, many of whom have had caseloads above 15 in each of the last three years.

Resignations among investigative child protective specialists increased in 2014 and 2015, but there were far fewer resignations in 2015 than in 2007 and 2008, possibly indicating that ACS’s efforts to support staff and improve working conditions have been effective. Consequently, average tenure of these workers in the most recent years studied has been much higher than either just before or after Nixzmary’s death.

Report prepared by Katie Hanna

Endnotes

1A report will not be accepted if:

- the subject is over 18 years of age

- the alleged perpetrator is not the child’s parent, legal guardian, or other person legally responsible for the child’s care, such as a foster parent or child care provider

- the allegation does not meet the state’s standard for abuse and/or neglect.

If the State Central Register finds that the person responsible for the alleged abuse or maltreatment of a child cannot be a subject of a report, but believes that the acts described in the call may constitute a crime or an immediate threat to the child’s health or safety, the central register must contact the relevant local law enforcement agency, district attorney, or other public official.

2A Child Safety Conference is triggered when one of the following situations occurs

- the child protective specialist and his/her supervisor have determined that safety concerns are serious enough that legal intervention of some kind may be necessary to keep the child safe

- an emergency removal has already taken place

- a parent expresses an interest in voluntary foster care placement

- a parent with a child who is in foster care or who has been released to a nonparent is pregnant or gives birth to another child

- a fatality occurs and there is a surviving sibling.

3ACS, Safeguarding Our Children: 2006 Action Plan, March 2006

4ACS, Safeguarding Our Children: Safety Reforms Update, November 2006

5New York City Department of Investigation, Report on ACS Policy and Practice Violations Identified in Three Child Welfare Cases and Related Analysis of Certain Systemic Data, May 2016: City of New York Office of the Comptroller, Audit Report on the Administration for Children’s Services’ Controls Over Its Investigation of Child Abuse and Neglect Investigations, June 2016

6New York City Council Oversight Hearing–Reporting Child Abuse and Neglect in New York City, October 2006

7New York City Department of Investigation, A Department of Investigation Examination of Eleven Child Fatalities and One Near Fatality, August 2007

8New York City Council Oversight Hearing—New York City’s Child Welfare System, September 2007

9Children’s Defense Fund and Children’s Rights, Inc., Components of an Effective Child Welfare Workforce to Improve Outcomes for Children and Families: What Does the Research Tell Us?, August 2006

10United States General Accounting Office, HHS Could Play a Greater Role in Helping Child Welfare Agencies Recruit and Retain Staff, March 2003

11Ibid.

12As a point of comparison, average caseloads in 1996, when ACS became its own agency, were 24.1.

13Vera Institute, Innovations in NYC Health and Human Services Policy: Child Welfare Policy, January 2014

PDF version available here.

Receive notification of free reports by E-mail