The Mayor’s Housing Plan Evolves

In December 2002, Mayor Michael Bloomberg announced the first iteration of his New Housing Marketplace (NHMP), a five-year plan to develop or preserve 65,000 units of affordable housing from fiscal years 2004 through 2008. The plan was expected to cost $3 billion. By October 2005—in the midst of last decade’s housing boom—preservation or development had started on nearly 35,000 units of affordable housing and the Mayor expanded NHMP to a 10-year program to develop or preserve 165,000 units by the end of fiscal year 2013. The new 10-year plan had a $7.5 billion budget and the Mayor hoped to “stem the increased costs of housing by catalyzing and harnessing the strength of the private sector.” Given the housing construction boom, the city proposed shifting the focus of the plan from preserving existing affordable housing to “developing unprecedented levels of new affordable housing.”1 (See side bar defining preservation.) A year and a half later, however, Lehman Brothers declared bankruptcy and the private housing market in the city began to crumble.

Since 2008, the Department of Housing Preservation and Development (HPD) has revised NHMP to address the changes in the economy and the housing market. In December 2008, the Mayor extended the deadline for starting the 165,000 units by one year to 2014. Modifications to the strategy included once again focusing more on preservation of units rather than new construction, which the city considered more feasible in times of economic distress. In addition, largely because of the types of housing the city has preserved, there has been an increase in the share of NHMP units for low-income families compared with moderate- and middle-income units. The high number of low-income units is boosted by the classification of a significant share of the Mitchell-Lama housing that has been preserved as low income, despite this being a historically moderate-income program. (See side bar on Mitchell-Lama preservation.)

Revisions to the original budget included the addition of $785 million in funding—more than doubling the funding provided through the reserves of the New York City Housing Development Corporation (HDC), the city’s housing finance agency, and recognizing new funding sources such as federal stimulus funds. At the same time, however, the budget for several funding sources, including the city’s capital program, was lowered. Lastly, the number of units expected to be created by programs that encouraged affordable development by leveraging the construction of new, market-rate housing have decreased.

This paper, produced at the request of Public

Advocate Bill de Blasio examines the shifting goals of the initiative—from constructing new housing to preserving existing affordable housing. It explores changes to how the housing has been and will be financed, examining in detail the city’s capital commitment, new funding sources, and the use of private market development programs. We also consider the prospects for the plan’s completion.2

Defining Preservation

The city preserves affordable housing through a variety of programs that rely on two strategies: extending the affordability requirements of existing affordable housing before they expire, or entering into new agreements to ensure affordability, while simultaneously financing needed improvements.

First, many preservation programs extend the affordability agreements of existing government-assisted housing that are set to expire. These include programs that target project-based Section 8 developments, Mitchell-Lama housing, or housing built with federal Low-Income Housing Tax Credits. The developer/landlord agrees to continue adhering to the affordability requirements and in exchange the city provides new financing for these projects through repair loans, tax incentives and/or mortgage restructuring.

Second, other preservation programs provide assistance—usually in the form of low-interest and/or forgivable loans—for moderate to gut rehabilitation of housing currently serving a range of incomes in exchange for agreements that ensure rents are affordable. These rehabilitated units often already serve low- or moderate-income households due to the relatively low market rents in the neighborhoods in which they are located. Affordability regulatory agreements apply to current and future vacant apartments. In addition, the city counts units from its programs to privatize city-controlled (in rem) vacant and occupied housing as preservation units. On average, about 70 percent to 80 percent of the preservation units have tenants.

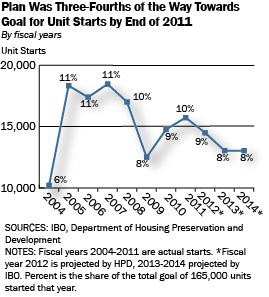

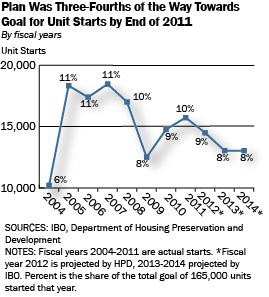

As of 2011: Three-Quarters of the Way to Housing Goal

Through the end of fiscal year 2011, eight years into the plan, the city and its partners have started 75 percent, or 124,418, of the planned NHMP units. Of those starts, 71 percent were completed by the end of fiscal year 2011. The highest share of unit starts took place from fiscal years 2005 through 2008. In fact, 43 percent of the projected 165,000 units were started in those four years when the housing market was at its peak. NHMP starts dipped most dramatically in 2009, going from 17,007 starts in 2008 to 12,500 starts in 2009. However, the number of starts has since begun rising again to 15,735 starts in fiscal year 2011. In order to reach its goal, the city needs to start approximately 13,500 units a year through 2014. Given its historic production levels, and barring any further housing market collapse, the city is likely to meet its overall goal.

Terms Used in This Analysis

Units Produced: Units counted toward NHMP goals can be either newly constructed or preserved. Throughout this paper “units produced” refers to both newly constructed and preserved housing.

Unit Starts: The city’s Department of Housing Preservation and Development counts a unit start when the financing for a new construction or preservation project has closed or an agreement imposing rent restrictions has been executed. Projects that are started count toward the city’s NHMP goals.

Unit Completion: In most cases this means that the Department of Buildings has certified the units are ready to be occupied by issuing a Certificate of Occupancy or Temporary Certificate of Occupancy. In some cases additional requirements must be met. For example, for the Article 8A Loan Program HPD must certify that the full scope of the rehabilitation is complete.

Affordability regulatory agreements: Affordability regulatory agreements describe the upper income limit for families eligible to live in the housing and the length of time that units must be rented or sold to households meeting income requirements, usually the length of the term of the loan providing the preservation financing. Unless otherwise noted, affordability requirements referenced in this paper are linked to the financial underwriting of the housing as determined by HPD, not the incomes of people actually living in the housing.

Financing Programs: Many of the units built or preserved are financed using multiple funding sources, including subsides through the city’s capital program, tax incentives and/or bond financing through HDC. Regardless of how many sources of financing are used, HPD attributes each unit to a single housing program based on the type of housing started.

City capital budget funding: City capital or city capital funding refers to support allocated through the city’s capital budget, which includes funds from city (both mayoral funds and Resolution A funds that are allocated by the City Council and Borough Presidents), state, and federal sources. In the case of NHMP, federal HOME funds are an important component. When used in this report, city capital budget funding excludes funding from the 421-a Fund, which is reported separately.

Original 10-Year Plan: This refers to the New Housing Marketplace Plan (and associated budget) the city released in 2006.

Revised 11-Year Plan: This refers to a revised version of the New Housing Marketplace Plan (and associated budget) the city released in 2010.

Changes in the Mix of Housing Units Under the Plan

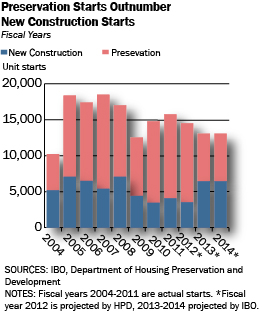

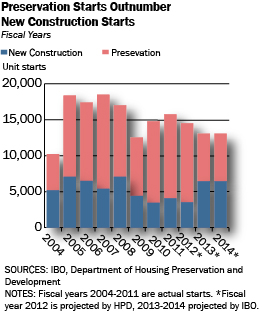

While on track to meet its overall goal on the number of units, the city has made significant changes in the mix of units. Driven by changes in the economic climate and downturn in the private housing financing market, a larger share of NHMP production is comprised of preservation units rather than new construction units. The city has also produced more low-income units than originally projected, largely due to the income-levels of the residents in the developments the city has been able to preserve. However, the city is less likely to meet the revised targets for new construction and middle-income units without a major shift in the types of units produced in the last few years of the plan.

Increase in the Share of Preservation Units.

The original 10-year plan projected that more than half of NHMP housing would be newly constructed housing rather than the preservation of existing affordable units, while the revised plan lowered the city’s goal to 36 percent of units to be new construction due to the weak housing market. By the end of fiscal year 2011, 35 percent of the NHMP starts were new construction and 65 percent were preservation. Even in the early years of the program when the share planned for new construction was higher, preservation deals outnumbered new construction fairly consistently throughout the plan, although there was a notable shift after the housing market crash: 72 percent of all starts from fiscal years 2009 through 2011 were preservation starts, compared with 61 percent from 2004 through 2008.

Despite recalibrating NHMP goals in 2010, HPD will still have to start a high share of new construction units in the last three years of the plan to reach its target of 64 percent preservation and 36 percent new construction units. In fact, because HPD projects that 76 percent of fiscal year 2012 starts will be preservation, 49 percent of starts (or at least 5,712 units a year) in the last two years would need to be new construction in order to reach that goal.3 HPD would have to reach new construction start levels close to that of 2006 in both 2013 and 2014 to meet the target. The ability to meet this goal will largely depend on how the city budgets its capital funds between new construction and preservation projects throughout the remainder of the plan, which is discussed in the financing section of this paper.

Preservation Units Often Have Shorter Regulatory Agreements. One important aspect of the increase in preservation units is that these projects often have shorter affordability agreement terms than new construction deals. Currently, most of HPD’s preservation programs carry a 30-year affordability agreement. However, several programs, including the Article 8A Loan Program, which is one of HPD’s most frequently used preservation programs, did not begin requiring affordability agreements for all projects until fiscal year 2011, even though these units are counted toward NHMP goals. While many but not all NHMP units that received Article 8A Loans were subject to regulatory agreements because they had previously received public financing or tax benefits (including the Mitchell-Lama projects and rental buildings participating in HPD’s asset management programs)—these agreements often ranged from only 15 years to 25 years. In addition, HDC’s programs to preserve the Mitchell-Lama housing stock can also have significantly shorter affordability terms. The majority of Mitchell-Lama projects preserved by HDC have a 30-year regulatory agreement but projects can opt out after 15 years. (See side bar for details on Mitchell-Lama Preservation).

New construction affordability agreements, however, can extend beyond the standard 30-year loan period to up to 50 years—something that both HPD and HDC have been increasingly including in Requests for Proposals when seeking developers for new projects.

Thus, the increase in preservation over new construction projects throughout the plan is likely to mean that a larger share of units will lose affordability restrictions more quickly—and be open to households with higher incomes— than if more new units were constructed under the plan. Rents in both housing constructed and preserved under the plan, however, are subject to rent regulation and landlords may only raise rents by amounts approved annually by the Rent Guidelines Board.

Increase in Low-Income Units. The high share of preserved units has helped drive an increase in the number of low-income housing starts for the housing plan, while starts for moderate income and middle income tenants have been below projections.

Low-income units are defined as those restricted to and affordable for families making 80 percent or less of the area median income (AMI), which is set by the federal Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) for the New York metropolitan area. Currently, HUD estimates the median income for a family of four to be $65,000, which includes counties neighboring New York City; while the median income for a family of four residing in New York City is $60,500, based on IBO’s analysis of the 2010 American Community Survey. The income threshold set by HUD to determine eligibility for affordable housing programs reflects not only income but also takes into account area housing costs. In New York it is increased to reflect the area’s high housing costs.4 Essentially, the median income used for eligibility is set to allow a family of four to cover 85 percent of the annual rent on a two-bedroom apartment with 35 percent of their income. Following this adjustment, HUD set the AMI for a family of four at $83,000, so an income below $66,400 (80 percent of $83,000) or lower would qualify the family for a low-income unit.

By the close of fiscal year 2011, 83 percent of the NHMP housing starts have been for low-income families (as federally defined) making 80 percent or less of AMI. The original NHMP projected that low-income units would make up 68 percent of the total. The higher share of low-income units comes at the expense of moderate (81 percent to 120 percent of AMI) and middle (121 percent to 180 percent of AMI) income units. Moderate-income units make up 7 percent of the NHMP housing starts thus far and middle-income units make up about 8 percent. The remaining 2 percent of units are classified as unrestricted.

According to its revised plan, HPD projects the final NHMP affordability split to be 76 percent low-income units, 11 percent moderate-income, and 10 percent middle-income units. Like goals for new construction, meeting this target will require a fairly significant change in the income mix of units started this fiscal year and in the next two years with a large uptick in the number moderate units. If starts are spread evenly throughout the end of the plan approximately 58 percent each year would need to be low income, 26 percent moderate income and 16 percent middle income, significantly more moderate income units produced than in any year yet throughout the plan.

|

Increase in Share of Preservation and Low Income Units |

|

|

Original 10

Year Plan |

Actual

2004-2011 |

Revised 11

Year Plan |

|

Start Type |

|

|

|

|

New Construction |

56% |

35% |

36% |

|

Preservation |

44% |

65% |

64% |

|

Ownership |

|

|

|

|

Rental |

71% |

68% |

69% |

|

Home

Ownership |

29% |

32% |

31% |

|

Affordability |

|

|

|

|

Low Income

(<80% AMI) |

68% |

83% |

76% |

|

Moderate

Income (81-120% AMI) |

11% |

7% |

11% |

|

Middle Income

(121-180% AMI) |

21% |

8% |

10% |

|

Unrestricted |

0% |

2% |

3% |

|

SOURCES: IBO; Department of Housing Preservation and

Development |

Hunters Point South Development to Generate Plan Units. One new development is expected to generate a significant share of moderate- and middle-income housing starts in the next couple of years. The Hunters Point South development, along the East River in Long Island City in Queens, is expected to produce at least 3,000 new units of affordable housing, with at least two-thirds planned to house moderate- and middle-income families. While even more development affordable to this income range would be necessary to meet both affordability and new construction goals, the Hunter’s Point South development would be a significant source of this housing. Construction of the housing is expected to begin this year.

Mitchell-Lama Deals Raise Housing Plan’s Preservation, Low Income Numbers

The preservation of apartments in Mitchell-Lama developments has been one of the most significant sources of NHMP units throughout the plan. Since 2004 the city has preserved more than 33,000 units of Mitchell-Lama housing, accounting for about 27 percent of the plan’s overall starts and about 40 percent of NHMP’s preservation starts. The Mitchell-Lama affordable housing program was established in the 1950s as a moderate income housing program for both rental and limited-equity cooperative developments. According to IBO’s analysis of data from the 2011 Housing and Vacancy Survey, about 73 percent of Mitchell-Lama rental units and 52 percent of Mitchell-Lama cooperative units are currently occupied by families that would qualify as low income.

Owners of Mitchell-Lama buildings, both rental and coop, can prepay their mortgage after 20 years and release their units from the program’s affordability restrictions.5 Through preservation financing, provided mainly through repair loans from HDC or HPD, mortgage restructuring from HDC, and other financing, the city can preserve the affordability of the housing for an additional 10 years to 30 years. The majority of the Mitchell-Lama units preserved have been coop developments (58 percent). Mitchell-Lama buildings are often large housing developments so the preservation of several projects can preserve the affordability of a large number of units.

Despite the income profile of current Mitchell-Lama occupants, HPD has classified 88 percent of the preserved NHMP Mitchell-Lama units as low income, an important factor contributing to the large share of low-income unit starts reported for the plan. Financing for some of the preservation deals has included Low-Income Housing Tax Credits or mortgages subsidized by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, which require that when residents move, the new occupants are low income. Additionally, according to HPD, the classification is appropriate because households moving in from the Mitchell-Lama waiting list often have incomes below that of existing tenants, although turnover is historically low. However, it should be noted that regulatory agreements in projects without Low-Income Housing Tax Credits or federally subsidized mortgages continue to allow moderate-income tenants to rent or purchase these units.

Financing the Plan

Budget Grows Overall, but Sources Shift.

Originally projected by the city to cost $7.5 billion over a decade, the price tag of NHMP has increased by $785 million to $8.3 billion—about a 10 percent increase. The growth comes, however, as the city has reduced its capital commitment to the plan by 13 percent from $4.5 billion to $3.9 billion. The most significant increases to the total current projected costs include:

- More than doubling the amount of HDC corporate reserves committed to NHMP from $548 million to $1.3 billion (HDC reserves include interest collected on loans, fees, and investment earnings);

- The addition of $150 million in new federal funds, mainly from economic and housing stimulus programs;

- The addition of $400 million for a special “421-a Fund,” half of which comes the Battery Park City Authority (BPCA) and half from city capital dollars (excluded from the city capital total); and

- An increase to the expense budget funding the city counts as part of NHMP by $100 million to nearly $1.4 billion. However, only about a third of these funds go towards costs related to the development of NHMP units; much of the spending is budgeted towards general housing code enforcement.

Other Funding Sources. Other funding sources for the plan include $695 million in leveraged value from the federal Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC).6 The city has also budgeted a total of $241 million from the New York City Acquisition Fund, a revolving loan fund created through a partnership between the city, private investment groups, and foundations to provide acquisition and predevelopment financing to developers. The acquisition fund’s current total is a third lower than originally budgeted in 2006, the result of both a reduction in the fund’s revolving credit agreement (from an initial $192 million to $150 million) as well as decreased demand for loan funds as the housing market slowed.

Another $138 million is budgeted from the New York City Housing Trust Fund, which is also funded through an agreement with the BPCA. The Lower Manhattan Development Corporation, which was established to promote the recovery of lower Manhattan after September 11, 2001 and is funded through federal Community Development Block Grants, has budgeted $54 million to the plan. Lastly, a Citywide Affordable Housing Trust Fund is planned to provide $20 million in funds for NHMP housing. The trust fund was established with proceeds from the sale of the Studio City development site on the far West Side of Manhattan as part of the Hudson Yards rezoning. This line was also reduced in the 11-year plan from $50 million due to a decrease in the sales price for Studio City and the added expense of constructing a school on the site.

Spending So Far. By the end of fiscal year 2011 a total of $5.6 billion had been spent on the plan, with the largest share ($2.7 billion) coming from the city’s capital program, followed by $1.0 billion from HDC’s corporate reserves (HDC also provides bond financing that the city does not count toward total NHMP cost), HPD’s expense budget contributed $1.0 billion, and the Low Income Housing Tax Credit provided $318 million (leveraged value). More than $150 million was spent from the New York City Acquisition Fund, $114 million from the city Housing Trust Fund, $41 million from the Lower Manhattan Development Corporation, and $61 million from the 421-a Fund. In addition, $114 million in new federal funds, including $85 million through the Tax Credit Assistance Program, $23 million through the Neighborhood Stabilization Program and $6 million through the Weatherization Assistance Program have also been spent on the plan.

New Housing Marketplace Plan Budget

Dollars in millions |

|

Funding Source |

Original

Plan |

Total

Spending

2004-2011 |

Total

Planned

FY12-FY14 |

Total NHMP |

|

Capital Budget |

$4,523 |

$2,693 |

$1,220 |

$3,913 |

|

Expense Budget |

1,264 |

1,004 |

378 |

1,382 |

|

Housing Development Corporation Reserves |

548 |

1,079 |

234 |

1,313 |

|

Low Income Housing Tax Credits (leveraged value) |

596 |

318 |

377 |

695 |

|

NYC Acquisition Fund |

360 |

151 |

90 |

241 |

|

NYC Housing Trust Fund (BPCA) |

130 |

114 |

23 |

138 |

|

Citywide Affordable Housing Fund |

50 |

0 |

20 |

20 |

|

Lower Manhattan Development Corporation |

50 |

41 |

13 |

54 |

|

New Sources |

|

175 |

375 |

550 |

|

421 A |

|

61 |

339 |

400 |

|

Tax Credit

Assistance Program |

|

85 |

0 |

85 |

|

Neighborhood

Stabilization Program I-III |

|

23 |

36 |

59 |

|

Weatherization Assistance Program |

|

6 |

0 |

6 |

|

TOTAL |

$7,521 |

$5,575 |

$2,731 |

$8,306 |

SOURCES: IBO; Housing Preservation and Development;

Housing Development Corporation; New York City

Acquisition Fund

NOTES: The Capital Budget line includes city and Federal

(HOME) funds. Capital Budget and HDC Reserves are net of

the 421-a Fund. The Expense Budget Line includes HPD's

Down Payment Assistance Program, federal "upfront

grants," and other costs flowing through the agency's

expense budget. Lines coming from the city expense and

capital budgets are as of the Fiscal Year 2013

Preliminary Budget. Figures may not equal total due to

rounding. |

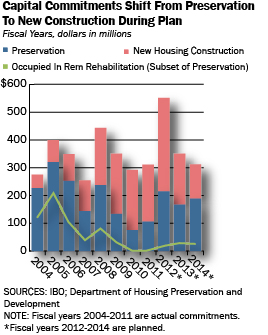

City Capital Funding Reduced. When the city announced its original 10-year plan in 2006, it projected that spending from its capital program would account for 60 percent of the total cost of the NHMP program. However, since the city initiated the plan there have been cuts to the city capital program in an effort to lower the city’s future debt service costs. There have also been cuts to the federal HOME Investment Partnership program, which is allocated through the city’s capital budget; HOME makes up about 30 percent of the city capital funding for NHMP.7 At the end of fiscal year 2011, funding from the city capital budget made up 48 percent of NHMP spending and the capital share is budgeted to remain close to that level through the end of the plan.

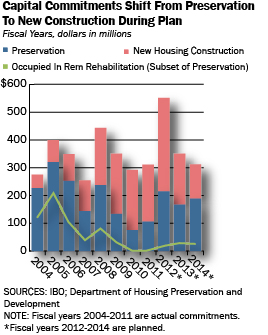

The city divides its NHMP capital spending into three main categories: preservation, new construction, and special needs housing, which includes both new construction and preservation of housing with supportive services for specific populations, such as people living with mental illness or HIV/AIDS. As of the end of fiscal year 2011, $1.4 billion from the city’s capital program (including both city and HOME funds) had been committed for preservation projects—53 percent of the total city capital funds. The city committed $820 million for new construction projects (30 percent of total capital funds from the city) and $433 million on special needs housing (16 percent), with the remaining $21 million going toward other costs associated with developing NHMP housing. When the supportive housing starts are divided into the preservation and new construction categories based on the type of project, the share spent on preservation increases to 56 percent while new construction accounts for 44 percent of the spending.

Use of City Capital Budget Funds for New Housing

Marketplace Plan

Dollars in millions |

|

Program Area |

Actual

2004-2011 |

Projected

2012-2014 |

Total

Current Projection |

|

Preservation |

$1,419 |

$553 |

$1,971 |

|

New Housing Construction |

820 |

489 |

1,309 |

|

Special Needs Housing |

433 |

172 |

606 |

|

Other Housing Support Investment |

21 |

7 |

27 |

|

TOTAL |

$2,693 |

$1,220 |

$3,913 |

SOURCES: IBO; Department of Housing Preservation and

Development

NOTES: Based on HPD Ten Year Plan Categories.

Preservation includes Occupied In Rem Rehabilitation costs. Includes city funds and noncity funds. Based on

Fiscal Year 2013 Preliminary Capital Commitment Plan.

Figures may not add up to total due to rounding. |

The share of city capital funds spent on preservation was highest during the first few years of the plan: from 2004 through 2006, the average share of capital funds committed for preservation projects was 77 percent. HPD’s Occupied In Rem Rehabilitation and Disposition programs, which helped preserve approximately 7,000 units, received a significant share of these funds. These programs can entail fairly large capital subsidies when compared with other preservation programs. For example, the Neighborhood Redevelopment Program and the Neighborhood Entrepreneur Program, two of the main Occupied In Rem Rehabilitation programs, provide subsidies of up to $120,000 per unit. These programs have been used less since 2008 because the city’s stock of in rem property has declined. In fact, only in fiscal year 2009—after spending on Occupied In Rem Rehabilitation dropped off—did the share of city capital funds committed for new construction increase to more than 50 percent.

More recently, capital commitments for new construction have outpaced preservation. In fiscal years 2009 through 2011 the share committed for new construction projects has averaged about 67 percent per year. Because per unit capital subsidies for new construction are often higher than those for most preservation projects, the share of new construction units—which has averaged around 28 percent—is considerably below the share of financing over the same period. For example, HPD’s Article 8A Rehabilitation Loan Program, one of the agency’s most frequently used preservation programs, provides a maximum capital subsidy of $35,000 per unit, while its new construction Low Income Program has a maximum capital subsidy of $70,000 per unit.

Looking ahead, capital commitments planned for 2012 through 2014 are also slightly higher for new construction than for preservation projects. Of the $1.2 billion in city capital funds (including HOME) budgeted for those years, 53 percent are planned for new construction projects, including the new construction of special needs housing (though the share of new construction units would be lower given the higher subsidy amounts). Most of this money is planned for fiscal year 2012. However, capital funds, both those for preservation and new construction, can roll from year to year based on actual project starts and it is likely some of these funds will be spent in the following years.

In order to meet its goal of having new construction make up 36 percent of all NHMP units, HPD will likely have to spend more on new construction subsidies going forward than in past years. While funding for new construction projects is rarely limited to HPD capital subsidies, given the average new construction capital subsidy over the past three years and the number of new construction units still needed, it is likely that the new construction funds planned in the city’s capital program will be inadequate to meet the new construction goal.8

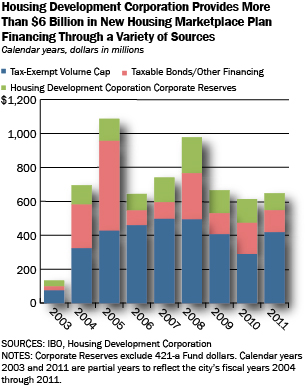

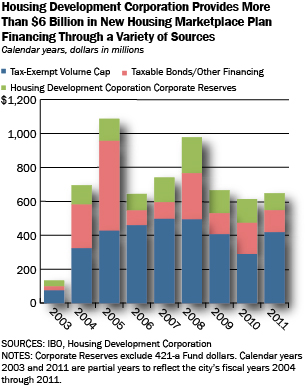

HDC Provides More Financing Than Expected. The Housing Development Corporation, the city’s housing financing agency, has provided significantly more financing than was budgeted at the start of the original 10-year plan and has been crucial to helping NHMP starts continue through the economic downturn. The city originally projected that HDC would spend $548 million from its corporate reserves (made up of fees, earnings and investments) on NHMP housing to help finance 42,000 units. At the end of fiscal year 2011, HDC had spent nearly $1.1 billion from its reserves to help finance 57,830 units (often in conjunction with HPD financing programs), an average of $140 million on NHMP housing in each year of the plan. HDC’s corporate reserves built from fees, earnings and investments, have mainly been used to finance low-interest second mortgages for NHMP projects receiving bond financing, as well as to fund the corporation’s Mitchell-Lama Repair Loan Program.9,10 High revenues, an average of $56.8 million a year during the past five HDC fiscal years, have bolstered corporate reserves, and according to HDC, allowed for its greater than anticipated investment into the plan.11

HDC’s contribution to the plan extends beyond its corporate reserves and includes more than $5 billion in bond financing, bringing HDC’s total support for NHMP to $6.2 billion. This includes $3.4 billion in tax-exempt bond financing (known as volume cap) used to finance NHMP units.12 Of the $500 million in tax-exempt bonds that HDC has been typically authorized to issue annually, an average of $412 million a year has been put towards meeting the NHMP goals since 2004. HDC has also used $1.7 billion in taxable bond and other financing to support NHMP production. Similar to the plan’s overall totals, 65 percent of the units receiving financing from HDC were preservation units and 35 percent new construction. Of its total $6.2 billion in financing for NHMP, $3.8 billion has been used to benefit 20,128 newly constructed units and $2.4 billion to preserve 37,702 units.

New Federal Bond Programs Used to Support NHMP. In addition to its traditional bond financing programs, HDC’s support for NHMP includes the proceeds from two new financing programs developed to help spur the U.S. economic recovery: the New Issue Bond Program (NIBP) and recycled bonds. As of the end of fiscal year 2011, HDC has used $262.2 million of NIBP bonds to help finance 3,752 units plus $285.6 million in recycled bonds to help finance 5,866 units (often in conjunction with other city subsidies and HDC bond financing). Some projects used both NIBP and recycled bonds. The federal Housing and Economic Recovery Act (HERA) of 2008 authorized both programs, as well as a one-time increase in volume cap, which HDC used to help finance preservation and new construction deals during the downturn.

The federal government created NIBP in order to provide liquidity in the housing bond market. It allowed housing finance agencies to issue bonds using fixed rates lower than those available on the public market.13 Through the program, housing finance agencies sold mortgage revenue bonds to the Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corporation (Freddie Mac) and Federal National Mortgage Association (Fannie Mae), which packaged and resold them to the U.S. Treasury. HDC received a $500 million allocation through NIBP that was issued by the end of calendar year 2011.14

The recovery act also authorized the use of recycled bonds for multifamily housing, a program HDC had lobbied for even before the housing market crash. Recycled bonds are generated by reusing tax-exempt volume cap. In order for projects financed with tax-exempt bonds to secure 4 percent “as of right” Low Income Housing Tax Credits, at least 50 percent of their development costs must be financed through tax-exempt bonds. However, most projects cannot support this debt and pay back some portion of the bonds after construction completion. Recycling allows HDC to reuse these early payoffs to finance other projects, without counting against the corporation’s volume cap.

Because recycled bonds do not secure tax credits, they do not carry the LIHTC requirement that all units be affordable to households making 60 of percent AMI or less. Recycled bonds do, however, carry the tax-exempt bond requirement that a portion of units be affordable—at least 20 percent affordable to households making 50 percent of AMI and below, or 25 percent of the units affordable to households making up to 60 percent of AMI. When HDC originally envisioned the program, it planned to use the bonds to finance mixed-income projects, with bonds subject to the volume cap financing the low-income units and recycled bonds providing financing for middle-income and market-rate units. While several of these projects were started, the housing market crash made the mixed-income deals challenging because it was difficult for developers to secure additional financing for the market-rate units. Instead, HDC has been using the program mainly to finance what it calls “workforce housing” in the South Bronx and Central Brooklyn. In most cases, 25 percent of the units in these projects are available to families making 60 percent of AMI and the rest of the units affordable to families making 80 percent AMI. Recycled bond have also been used to help preserve Mitchell-Lama projects that are not eligible for LIHTC financing because household incomes exceed the tax-credit limits, but, meet the lower threshold required for recycled bonds.

New Federal Awards Boost Funding for Plan. In addition to the bond programs authorized through the recovery act, the city also received several grants through the federal government’s economic stimulus legislation and other programs to help alleviate the effects of the housing market crash on the development of affordable housing. The new awards are projected to help finance more than 3,600 NHMP units with $85 million through the Tax Credit Assistance Program, $59 million through three rounds of Neighborhood Stabilization Program grants, and $6 million from the Weatherization Assistance Program. These funding sources provide important gap financing for the NHMP after the crash of the housing finance market.

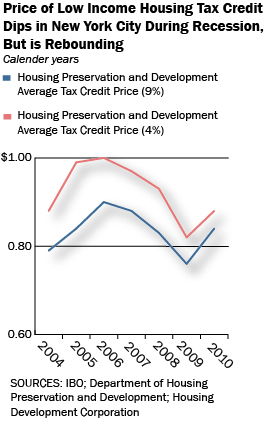

Filling the Gap in Tax Credit Funding. In the original 10-year plan, the city assumed that the proceeds from the sale of federal Low Income Housing Tax Credits would contribute $596 million to NHMP goals. The total current projection is higher at $695 million, despite a sharp decline in the price of tax credits during the worst of the financial crisis. Thanks to a federal stimulus funded program, the Tax Credit Assistance Program, to help fill funding gaps during the slump and a subsequent rebound in the market for tax credits the LIHTC has remained a significant funding source for NHMP housing.

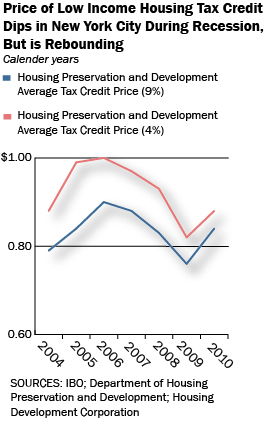

The net proceeds of the sale of tax credits (the leveraged value) depend on the strength of the tax-credit market. In 2006, when the original 10-year plan was introduced, average local tax credit prices were high—$1.00 for the 4 percent credit (received “as of right” through the use tax-exempt bonds) and $0.90 for the 9 percent tax credit (awarded competitively by HPD). However, in 2008 and 2009, the price of the tax credits fell nationwide. While New York was not hit as hard as other areas—lows in New York City ranged from $0.76 for the 9 percent credit to $0.82 for the 4 percent—the drop opened financing gaps for developers.

In response, the federal government created TCAP using American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) funds in 2009. HPD received a sub-allocation of $85 million from New York State, which it awarded on a competitive basis to projects with LIHTC financing (either 4 percent or 9 percent). In awarding the funds, HPD prioritized large projects, projects that could be completed by the TCAP deadline of February 2012, and projects that already had federal prevailing wage requirements because TCAP funding required that the developers pay prevailing wages. Prevailing wages are set by the government usually based on union contracts and are often much higher than non-union market wages. A total of 10 projects containing 1,136 units received awards with the majority of units located in projects developed through HPD’s supportive housing and low income rental programs. Since 2009, however, the price of the tax credit has been rebounding. By 2010 it was back to $0.84 and $0.88 for the 9 percent and 4 percent, respectively and continued to rise through 2011, helping to increase the leveraged value of LIHTC in the NHMP budget.

Neighborhood Stabilization Program Targets Foreclosed and Abandoned Properties. New York City received three awards as part of the federal government’s Neighborhood Stabilization Program (NSP) providing financing for a projected 1,054 units of housing. NSP provides funding for localities to purchase and redevelop foreclosed and abandoned residential properties, both single and multifamily, as well as fund some down payment assistance. The first NSP award, for $24.3 million, was authorized by HERA in 2008, the second, for $20.1 million, by ARRA in 2009, and the third, for $9.8 million by the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act in 2010. In addition, New York City received $5 million through two sub-awards of New York State’s NSP grants ($1.9 million for NSP I and $3.1 million for NSP III).

By the end of fiscal year 2011, HPD had entered into an agreement with the federal government on spending NSP I funds and prepared budgets for NSP II and III. However, financing has closed on just 258 NSP I units as of the end of fiscal year 2011. The majority of these units (160) are part of HPD’s Owner Abandoned Multifamily Property Strategy through which HPD provides financing to help new owners purchase distressed multifamily housing to provide rental housing to low-income families. The remaining 98 units are part of HPD’s Real Estate Owned program through which HPD finances the acquisition and rehabilitation of foreclosed homes by nonprofit organizations. This housing is then sold to households making less than 120 percent of AMI. The federal government has similar goals for NSP II and NSP III funds, which must be spent by February 2013 and March 2014, respectively.

ARRA Program Weatherizes 1,448 NHMP Units. The city is also applying $6 million of a $15 million grant through ARRA Weatherization Funds from the Department of Energy to NHMP housing units. The funds were awarded to Community Weatherization Partners, a joint venture formed by the Local Initiatives Support Corporation NYC and Enterprise Community Partners.15 The program has helped 1,448 units of low-income housing become more energy efficient by the end of fiscal year 2011. Priority for the program is given to buildings taking part in HPD’s LIHTC Year 15 Preservation Program, which provides eligible buildings reaching the end of the initial 15-year tax credit compliance period with interest-free loans to help maintain the long-term affordability of the housing.

Market Driven New Construction Levels Off. Along with direct subsidies and bond financing, when the city introduced the 10-year NHMP in 2006, it also planned to capitalize on the strength of the private housing market to encourage the development of affordable housing. In particular, the city planned to rely on its inclusionary housing program and its 421-a Affordable Housing Program (also referred to as the 421-a negotiable certificate program) to spur market rate development and provide the linked affordable units.16 The subsequent faltering private housing market and the elimination of the 421-a Affordable Housing Program, however, have sharply curtailed the role of these programs in NHMP production.

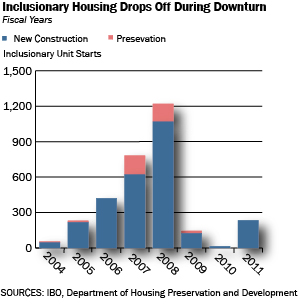

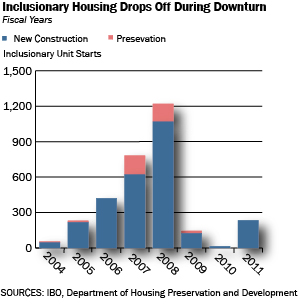

Inclusionary Housing Picks Up After Slowdown. According to the original 10-year plan released in 2006, the city planned to create or preserve 6,000 units through inclusionary housing—a program that allows greater market-rate housing density in areas rezoned by the city in exchange for the new construction or preservation of permanently affordable housing either on or off site. By the end of fiscal year 2011, developers had started close to 3,100 units of inclusionary housing that are part of NHMP. Of the inclusionary units created, 88 percent are new construction units and 12 percent are preservation units. The inclusionary housing program hit its peak for NHMP production in fiscal year 2008, with more than 1,200 units started. The majority of these units were attributed to new construction in the rezoned areas of Hudson Yards on the West Side of Manhattan and preservation deals in Greenpoint-Williamsburg on the waterfront of the East River in Brooklyn. By its nature, however, the success of the inclusionary housing program relies on a strong housing market to spur the creation of the market-rate housing that brings along with it the affordable development. Thus, as the housing market slowed down, unit starts in the inclusionary housing program fell to 144 in fiscal year 2009 and only a handful of units in 2010. However, by the end of 2011 more than 200 inclusionary units had been started, reflecting a modest pickup in the housing market.

421-a Affordable Housing Program Ends, Replaced by 421-a Fund. The 421-a Affordable Housing Program, which ended in 2007 when changes to the city’s 421-a tax exemption program took effect, provided equity to affordable housing developers through the sale of negotiable certificates to the developers of market-rate housing, thus qualifying market rate development for real estate tax exemptions. The issuance of 421-a negotiable certificates financed the completion of 3,258 units of affordable housing. Because projects were already in the development pipeline and had entered into regulatory agreements when the program ended, the program continued to support construction of affordable housing through fiscal year 2009 and then dropped off, although additional certificates remain.

As the housing market faltered and financing dried up, several developers that had entered into agreements with the city to start affordable housing that would generate certificates were unable to obtain financing for their projects. At the end of fiscal year 2011, 373 units of affordable housing that were planned to generate certificates were on hold and the certificates have not yet been issued. In addition, like inclusionary housing, the 421-a certificate program relied on a strong housing market to drive the demand for certificates that were already generated. As the housing crisis stalled market rate development, some housing developers were left with certificates they were unable to sell. At the end of fiscal year 2011, however, HPD reported it was beginning to receive requests to issue certificates again, a sign that the market for the remaining certificates may be warming.

The legislation that eliminated the 421-a Affordable Housing Program also created an affordable housing trust fund, the“421-a Fund,” with priority for units in the city’s neighborhoods with the highest concentrations of poverty. The $400 million fund is financed half through the city’s capital program and half through payments made by the Battery Park City Authority to HDC. When originally announced in 2006, the fund was to be financed through increased tax revenue generated by revisions to the 421-a tax exemption program intended to make it less generous. In fiscal year 2011, more than four years after the City Council authorized the creation of the fund, the city and the Battery Park City Authority began to make allocations to finance housing. (See IBO’s May 2011 Memo: Background on 421-a Fund for details on the creation of the fund.) Nearly $61 million from the fund had been spent by the end of fiscal year 2011 ($33.1 million by HDC and $27.4 million committed by HPD), which will help to provide financing for more than 1,200 NHMP units.

Although the city counts inclusionary and 421-a certificate unit starts, which do not receive direct city subsidies, toward the NHMP goal, it does not include in its NHMP total units started under the 20 percent affordable requirement in the 421-a “Exclusion Zone” (Manhattan and mainly the waterfront areas in Brooklyn and Queens) where projects receive property tax exemptions if at least 20 percent of the units are affordable to low-income households.

City Expense Budget Funding of NHMP Increases. The city’s expense budget has also been a significant source of NHMP funds, according to HPD’s budget for the plan. Only about one-third of these funds, however, provide direct financing for development of housing units in the plan. About $1 billion has been spent on NHMP from the city’s expense budget from fiscal years 2004 through 2011. Another $378 million is budgeted for the remainder of the plan. The total current projection of close to $1.4 billion, with more than 70 percent coming from the federal Community Development Block Grant, is a 9 percent increase in the amount budgeted when the original 10-year plan was introduced. These costs include both HPD personnel costs (about 60 percent of the costs) and other than personnel expenditures.

Most Expense Funds for Maintenance, Anti-Abandonment Programs. The largest share of the expense funding budgeted over the course of the plan ($726 million) supports enforcing the city’s housing maintenance code, including HPD’s Emergency Repair Program, Alternative Enforcement Program, Division of Maintenance and general code enforcement program. HPD’s budget for the code enforcement programs has been consistently rising over the past several years. In addition, another $153 million is budgeted over the course of the plan to support HPD’s anti-abandonment programs and housing litigation. Smaller one-time federal grants, for example for HPD’s lead remediation programs, are also included.

New Housing Marketplace Plan

Expense Budget

Dollars in millions |

|

Program Area |

Actual

2004-2011 |

Projected

2012-2014 |

Total Current Projection |

Code Enforcement

and Emergency Repair |

$503 |

$223 |

$726 |

Housing Finance and

Other Preservation Programs |

192 |

72 |

264 |

|

Division of Alternative Management |

159 |

42 |

202 |

Anti-Abandonment

and Housing Litigation |

117 |

36 |

153 |

|

Down Payment Assistance |

27 |

5 |

31 |

|

Other Grants |

6 |

- |

6 |

|

TOTAL |

$1,004 |

$378 |

$1,382 |

SOURCES: IBO, Department of Housing Preservation and

Development

NOTES: Based on FY2013 Preliminary Budget |

According to HPD, these expense budget-funded programs are important to the NHMP plan because they help preserve the city’s current supply of affordable housing; they are included in the analysis to reflect the city’s estimate of the cost of its housing plan. IBO believes these funds should not be credited towards the NHMP budget, however, because the programs do not provide financing to build or preserve units counted toward the NHMP goal. Excluding the code enforcement and anti-abandonment funds would reduce the overall NHMP budget by $885 million to $7.4 billion.

Other Expense Budget Costs More Directly Related to NHMP Goals. From its expense budget HPD has budgeted a total of $264 million over the 2004 through 2014 period for housing finance and other preservation programs, which includes personnel costs for the agency’s housing finance programs, its Division of Architecture, Construction and Engineering, as well as noncapital eligible expenditures for some of the agency’s preservation capital programs, such as the Third Party Transfer and 7A Management programs. Another $202 million is projected over the course of the plan for HPD’s Division of Alternative Management, which is responsible for returning buildings currently under city control to private ownership; and $31 million for HPD’s Down Payment Assistance Program.

The Down Payment Assistance Program is funded mainly with federal HOME funds. It provides eligible, low-income households with $15,000 toward the down payment or closing costs of a one- to four-family home, condominium, or cooperative. From fiscal year 2004 through the end of fiscal year 2011, 1,467 families had received assistance through this program; these units are counted towards the NHMP goal. No funds have been budgeted for this program in fiscal years 2013 and 2014, however. According to the Mayor’s Office of Management and Budget, if federal HOME funds become available and a there is sufficient demand some funds may be shifted to the program.

Future Federal Funds at Risk. In addition to the temporary federal stimulus funding received in response to the economic downturn, ongoing federal sources make up a significant share of the NHMP budget and recent and future cuts at the federal level make the funding stream uncertain. As previously mentioned, federal HOME funds have accounted for 30 percent of the city’s capital spending on NHMP from fiscal years 2004 through 2011 and are budgeted to make up 35 percent in fiscal years 2012 through 2014. Similarly, the federal Community Development Block Grant made up 71 percent of the expense budget funding for NHMP through the end of fiscal year 2011 and is budgeted to provide 76 percent of such spending in the remaining years of the plan.

However, both of these funding sources have been cut repeatedly and further cuts are possible. HPD’s CDBG allocation was cut by 10 percent after overall CDBG funding was cut by 16 percent in the federal fiscal year 2011 budget. The city’s CDBG allocation was cut again by 8 percent in federal fiscal year 2012, although it is unclear at this time whether HPD’s allocation will be reduced by the full 8 percent as other city agencies also receive CDBG funding. In addition, the city’s HOME allocation was cut by 45 percent in federal fiscal year 2012. HPD will likely feel the full effect of the HOME cuts, which will mostly affect the production of supportive housing as these programs receive the most HOME funding.

Because federal HOME and CDBG funds can roll from year to year, allowing HPD to draw on prior year’s allocations that were not fully spent, and HPD is already eight years into the plan, the agency may be able to mitigate the effect of these cuts on NHMP goals. However, these funding sources can still be considered at risk for meeting the NHMP goals, as well as for future affordable housing development in the city.

Another federal funding source that HPD had briefly budgeted to help cover $47 million in NHMP costs was the National Affordable Housing Trust Fund. The federal housing trust fund was created in 2008 through the recovery act with its funding based on a percentage of new business received by Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae. However, when Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae were taken over by the Federal Housing Finance Agency, the funding was suspended. While President Obama budgeted $1 billion for the fund and there have been several House and Senate bills proposing new funding sources, a final funding vehicle to replace the Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac funds has yet to be identified. Because it seems unlikely that the city will receive a National Affordable Housing Trust fund allocation by the end of the NHMP plan, HPD has eliminated it as a funding source.

Prospects for Meeting Housing Production Goals

Eight years into the plan, the city has started 75 percent of its projected 165,000 NHMP units. Taking advantage of an increased commitment from HDC, as well as benefiting from new federal stimulus funds and programs, the city has been largely successful with keeping the plan on track in terms of overall housing starts. This comes despite the crash of the housing market and its negative effects on private market-induced affordable housing production, as well as significant cuts to the city’s capital program.

The type of NHMP housing produced, however, is likely to be overwhelmingly preservation units, rather than newly constructed housing given the changes in the economic environment during the plan. In addition, the mix of households eligible for these units has changed with a higher share of units affordable to federally defined low-income households, as opposed to moderate- and middle- income families because of this shift to a higher share of preservation units. Although with three years left in the plan the city has some time to increase the share of new construction units, given historic production and budgeted capital amounts it seems unlikely it will meet its overall goals in these areas. Additionally, two key federal funding streams, HOME and CDBG, are at risk.

This report prepared by Elizabeth Brown